Liu Na’ou

劉吶鷗/刘呐鸥

1905-1940

Présentation

par Brigitte

Duzan, 12 février 2024, actualisé 16 février 2025

| |

Liu

Na’ou |

|

Écrivain

représentatif du mouvement néo-sensationniste des années

1930 à Shanghai, Liu Na’ou a également réalisé quelques

courts métrages inspirés du cinéma étranger.

Sa

naissance est restée controversée pendant longtemps :

d’après le « Historical

Dictionary of Modern Chinese Literature »

de Li-hua Ying,

il serait né au Japon, mais,

selon

Isabelle Rabut,

il était Taïwanais de mère japonaise, et éduqué au Japon. Il

est effectivement né à Tainan, le 22 septembre 1905, et il a

vécu là jusqu’à l’âge de 16 ans, après quoi il est parti

poursuivre ses études au Japon. C’est sa mère qui lui a

longtemps fourni son « argent de poche ».

À Tokyo,

il étudie l’anglais, puis, de retour à Shanghai en 1925, il

s’inscrit en 1926 à l’université Aurora (震旦大学)

pour étudier le français. C’est là qu’il rencontre les

poètes Dai Wangshu (戴望舒)

et Du Heng (杜衡)

ainsi que l’écrivain Shi Zhecun (施蛰存).

C’est avec eux, après de nouveau un bref séjour au Japon en

1928, que Liu Na’ou fonde en 1932 la revue mensuelle

Xiandai, sous-titrée « Les contemporains » (《现代》杂志),

dirigée par Shi Zhecun, après quoi Dai Wangshu part en

France pour étudier à l’Institut franco-chinois de Lyon.

Traductions, édition et nouvelles

Jusqu’en

1934, sous l’égide de ses cofondateurs, la revue publie des

textes et poèmes du courant néo-sensationniste (新感觉派) :

courant calqué sur le mouvement moderniste japonais

Shinkankakuha (新感覚派)

lancé en 1924 par des jeunes écrivains autour, en

particulier, de Kawabata que Liu Na’ou avait rencontré à

Tokyo. Nouvelle littérature inspirée entre autres par

l’œuvre de Paul Morand érigé en symbole de l’ère nouvelle,

dont Liu Na’ou a d’ailleurs traduit des récits.

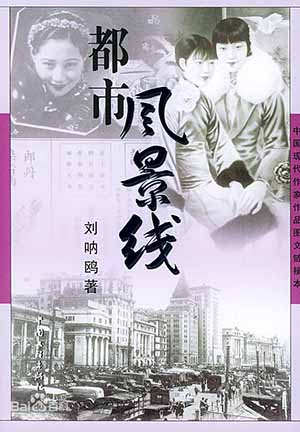

Entre-temps, en avril 1930, il avait publié le recueil de

nouvelles « Paysage urbain » ou « Ligne d’horizon urbain » (Dushi

fengjing xian《都市风景线》),

traduit par Marie Laureillard « Scènes de vie à Shanghai »

(voir Traductions ci-dessous) : des histoires d’amour qui

reflètent l’atmosphère de Shanghai comme épitome de la vie

moderne, entre désir dramatisé et culture matérielle

exacerbée. Shanghai était en effet pour lui une ville

métissée, entre Orient et Occident, qui exerçait sur lui un

attrait ambivalent : dégoût pour son luxe excessif et son

atmosphère décadente, mais aussi fascination pour la magie

qu’elle opérait (上海的“魔力”).

Ces

nouvelles ont été initialement publiées dans la première des

revues que Liu Na’ou a créées, en septembre 1928 : « Le

train sans rails » (《无轨列车》杂志).

Le recueil était inspiré du film de Fritz Lang sorti en

1927 : « Metropolis » (en chinois

《大都会》).

Dans l’édition de 1930, le recueil portait en sous-titre

« Scène ».

Dushi fengjing xian

Le recueil

est aussi à replacer dans le contexte de la fugace maison

d’édition et librairie qu’il avait fondée à Shanghai en

1928, « Culture de l’éros » (Seqing wenhua

《色情文化》),

où il publia des nouvelles japonaises - maison d’édition et

librairie qui furent bien vite interdites par le

gouvernement nationaliste.

Cinéma

En 1932,

Liu Na’ou fait une incursion dans le domaine

cinématographique : il signe des critiques, s’intéresse à

l’écriture de scénarios et dirige une revue, « Cinéma

moderne » (Xiandai dianying《现代电影》).

Il produit même en 1938 un film inspiré de « La Dame aux

camélias » (Chahua nü《茶花女》),

à la compagnie Guangming (光明影业公司).

Il s’agit de l’un des derniers films réalisés à Shanghai par

Li

Pingqian (李萍倩),

après la destruction des studios de la Mingxing par les

bombardements japonais lors de la bataille de Shanghai.

Chahua nü

Assassinat

Le 3

septembre 1940, alors qu’il était rédacteur en chef d’un

journal nationaliste (《国民新闻》),

édité par le gouvernement de Wang Jingwei (汪精卫政权),

il est assassiné à la porte de l’hôtel Jinghua (上海京华饭店)

sans que l’on sache encore trop pourquoi : sans doute parce

qu’il était soupçonné d’être un traître par les

nationalistes, mais peut-être aussi bien en raison de ses

liens avec les Japonais. Il avait 35 ans.

Traductions en français

- De

l'inconvénient d'avoir tout son temps, dans Le Fox-trot

de Shanghai et autres nouvelles chinoises, trad.

Isabelle Rabut et Angel Pino, Albin Michel, « Les grandes

traductions », 1996, p. 295-306.

- Scènes

de vie à Shanghai (Dushi

fengjingxian《都市風景線》),

recueil de douze nouvelles sur les quinze du recueil

original, traduit et postfacé par Marie Laureillard, Serge

Safran, 2023.

1. Jeu

游戏

2.

Paysages

风景

3. Flux

流

4. Un

cœur ardent

热情之骨

5.

Rituels et hygiène

礼仪和卫生

6. Deuil

残留

7.

L’équation

方程式

8. Sous

les tropiques

赤道下

9. La

couverture ouatinée

绵被

10.

Tentative d’assassinat

杀人未遂

11. A

Lady to keep you company

12.

L’éternel sourire

永远的微笑

| |

Dushi fengjingxian,

rééd. 2004 |

|

Traductions en anglais

- Diary,

tr.

Edward M. Gunn, in Yung-sheng Yvonne Chang, Michelle Yeh and

Ming-ju Fan eds., The

Columbia Sourcebook of Literary Taiwan, Columbia

University Press, 2014, 56-57.

-

Scenery,

tr. Travis Telzrow, MCLC Resource Center Publication, June

2019.

- Attempted Murder,

tr. Paul Bevan, in

Intoxicating Shanghai–An Urban Montage: Art and Literature

in Pictorial Magazines during Shanghai’s Jazz Age,

Brill, 2020, 253-63.

- Urban Scenes (《都市風景線》),

tr.

Yaohua Shi and Judith Armory, Cambria, 2023.

Note sur

l’écriture de Liu Na’ou

Quiconque

tente de lire les nouvelles de Liu Na’ou en chinois ne peut

qu’être dérouté par la langue, qui ne correspond pas au

« mandarin standard ». On a parlé d’exotisme, mais il est

intéressant d’aller un peu plus loin.

Dans son

article sur les écrits de Liu Na’ou dont on trouvera

ci-dessous un extrait significatif, l’auteur Ying Xiong

explique que, ayant été éduqué au Japon, Liu Na’ou avait le

japonais pour langue maternelle, et que son chinois était

pour le moins hésitant, ce qu’ont corroboré les témoignages

de ses amis, dont le néo-sensationniste Shi Zhecun (施蛰存).

En même temps, Ying Xiong souligne que, quand Liu Na’ou est

rentré en Chine, en 1927, le chinois lui-même était dans une

phase de transition après l’adoption encore récente du

baihua, de même que la littérature moderne. Donc la

langue de Liu Na’ou et son style ainsi que ses nouvelles

sont à reconsidérer dans ce contexte.

(les

passages soulignés en gras sont de mon fait.

BD)

From Taiwan to China via Japan

Around 1928, Liu Na’ou shuttled back and forth between

different territories. Unsure where to stay, Liu finally

decided to settle in Shanghai. His determination to stay in

Shanghai had two dimensions: the economic and cultural

advancement of Shanghai; and, in sharp contrast, the

cultural backwardness of Taiwan. Shanghai in the 1930s was

among the top ten cities in the world, a centre that could

lay claim to modern industry, burgeoning finance, and

extremely busy ports. As early as 1896, a year after the

inception of film in France, western films appeared in

Shanghai, bringing the earliest practice of the movie to

China. From that time on, the development of Shanghai was

inscribed with the growth of the Chinese film industry. In

1927, the year Liu arrived in Shanghai, the city witnessed

the debut of the talking film, only one year after its debut

in Hollywood. The maturity of cultural capitalism not only

lured Liu from Tokyo but also laid the foundations for his

later career. However, in sharp contrast, at the time,

Taiwan was under the colonial government of Japan. Native

Taiwanese could not receive a proper education due to the

imperial education system introduced by the Japanese

colonial government. Colonial discrimination worked to block

the advancement of the

native Taiwanese. For this reason, many opted to study in

either Japan or China. Against this background, Liu went to

Japan in search of educational opportunities. Most of the

pages in the newspapers in Taiwan were printed in Japanese:

only a quarter of the space allocated to Chinese.23 Chinese

journals at the time were preoccupied with classical

poetry.24 It is not surprising that Liu chose to go to

Shanghai rather than return to Taiwan. “Go back home! Go

back to the warm south” and “The banian trees are the origin

of our happiness, reflecting the strength of people living

in the South” are two quotes cited by many Taiwanese

researchers to show Liu’s Taiwanese nationalism. […] The

above quotations are the only two occasions Liu explicitly

expresses his love for Taiwan. The former was written when

his career in Shanghai was jeopardized, while the latter was

composed when he went back to Taiwan for his grandmother’s

funeral. In general, Liu stayed in Shanghai for pragmatic

considerations. […]

From Beijing to Shanghai

In contemporary scholarship addressing Liu’s modernist

writings, there has been a trend to associate his work

exclusively with semi-colonial Shanghai, stressing the

overwhelming effect of Shanghai on his writings. However,

Beijing, as a part of the Chinese power, also exerted a

great influence on Liu’s writing, not only providing him

with a personal relationship upon which to forge his later

career but also offering a direct Chinese experience on his

writing. Liu’s literary career encapsulated the social and

political changes in China of the late 1920s. Rather than

being isolated from the rest of China, Shanghai’s cultural

exuberance was formed in part as a result of political

struggle as well as social change in China.

Prior to the beginning of his literary career in Shanghai,

Liu embarked on a pilgrimage to Beijing. This

seldom-mentioned experience was carefully recorded in Liu’s

diary in 1927. On 28 September 1927, Liu set out by sea and

arrived in Tianjin on 1 October. From Tianjin, Liu took a

train to Beijing, where he spent the next two months. It was

not until 3 December that Liu returned to Shanghai. The days

spent in Beijing offered Liu a chance to experience

first-hand contact with Chinese culture and Chinese

literature for the first time. The cultural atmosphere in

Beijing made Liu realize that the reason he could not get a

feeling of the real China from the literary texts he used to

study was because he had not actually been to Beijing. In

other words, the trip to Beijing reflected the start of

Liu’s understanding of China. The significance of his trip

to Beijing is also evident in the fact that during this

trip, Liu established the personal connections necessary for

his later career in Shanghai. In other words, his experience

of Beijing, to some extent, laid the foundations for his

career. In Beijing, he encountered Feng Xuefeng (冯雪峰),

who later became a significant figure in the Chinese

Communist Party. After settling in Shanghai, Feng published

many books through Liu’s Publishing House, at one time

working there as a main editor. Many members of Liu’s

Publishing House, including Feng, Yao Pengzi (姚篷子

1891–1969), and Xu Xiacun (徐霞村1907–1986)

all fled Beijing for Shanghai when the political and

cultural situation in Beijing deteriorated. Post-1927,

Beijing, the cultural centre of China, was under the

political control of the Kuomintang. The year Liu settled in

Shanghai saw a large number of writers leave Beijing and

other places for Shanghai, in order to avoid political

prosecution. Lu Xun (鲁迅),

Hu Shi (胡适),

Guo Moruo (郭沫

若),

Mao Dun (茅盾),

Jiang Guangci (蒋光慈),

and many other significant figures in Chinese modern

literature arrived in Shanghai in 1927. Concomitant with the

decline of the Beijing era was the birth of a new modern

Shanghai, which sustained Liu’s image of China in the years

that followed. Liu’s Publishing House rode the trend of

intellectual mobility of the China of 1927.

The advancement of the cultural market in Shanghai which was

largely held as the enzyme for Liu’s literary career, should

not be separated from the cultural accumulation in Beijing.

Liu’s trip to Beijing also directly contributed to his

writing material. According to his diary, while living in

Beijing, Liu frequently visited a prostitute named Lü Xia (绿霞)

who may have inspired Liu’s “Etiquette and Hygiene” (礼仪与卫生),

which depicts a similar experience with a prostitute named

Lü Di (绿弟)

[…]. Liu’s visit to Lü Xia in Beijing ended in failure….

Liu’s nasty mood in Beijing was reflected in the male

protagonist Yao Qiming’s evaluation of modern prostitution

[in the story] : “there should be a thorough reformation,

since they [prostitutes] are not professional in dealing

business, demanding improvements on simplicity and

efficiency. They seem to deliberately decorate their

occupations with unnecessary rituals and trivialities,

lacking efficiency.” In the end, Liu chose to live and work

in the cosmopolitan city of Shanghai, which was home to

migrants from all over the world. In fact, by 1927, Shanghai

had attracted many Taiwanese besides Liu. For example, Zhang

Wojun (张我军

1902–1955), the father of Taiwanese modern literature,

arrived in Shanghai as early as 1923. Huang Chaoqin (黄朝琴

1897–1972), who later worked in foreign diplomacy for the

Republic of China, arrived in Shanghai around the same time

as Liu, and eventually became one of his neighbours. As

such, the birth of Liu’s writing should be located in the

historical background of East Asia in the 1920s and 1930s,

fully taking into account its cultural mobility. Liu’s

writing was initially propelled by two cultural and

geographical torrents, one flowing from Taiwan to China via

Japan, the other from Beijing to Shanghai.

The Modernist Writing of “Intertwined Colonization”

The modernization of language played a significant role in

the establishment of nationalism. As pointed out in

contemporary studies; “In spite of their reading knowledge

of foreign literatures, modern Chinese writers did not use

any foreign languages to write their work and continued to

use the Chinese language as their only language.”

Reading foreign literature and practicing writing in foreign

languages only acted as a means through which the writers

could acquire new knowledge. It was thus an instrument that

served nationalism. Leo Ou-fan Lee triumphantly declared

that unlike some African writers who were forced to write in

the language of the colonizer, Chinese writers fortunately

never confronted such a threat. Therefore, he drew the

conclusion that Chinese modernist writers’ Chinese identity

was never in question. The ‘Chinese modernist writers’ Leo

Ou-fan Lee referred to included Liu Na’ou, who was one of

the core writers of ‘modern Shanghai.’ Notwithstanding this,

inside China, or even Shanghai, intellectuals’ circumstances

differed in countless ways. For Liu, the strategy of

language not only reflected his connection with Chinese

culture and literary history but also revealed the colonial

reality of Japan and Taiwan.

Heritage of May Fourth Spirit

All of Liu’s works were written in Chinese. There is no

denying that his choice to write in Chinese was related to

the objective requirement for him to publish novels in

China. But there were other reasons hidden deep in his

cultural background. Although Liu’s Japanese was more

fluent than his Chinese, and most of his diary was written

in Japanese, he did not publish his works in Japanese.

This was a common strategy adopted by many Taiwanese writers

during the period of Japanese colonization. Liu insisted on

writing his stories in his ‘awkward Chinese.’ According to

his diary, by 1927 he had received a Japanese education for

more than ten years, but this did not essentially hinder his

Chinese writing. Without the special attention he paid to

Chinese writing, apart from the normal education in

Japanese, he could not have published his first Chinese

collection shortly after he finished his overseas study in

Japan. Liu also actively encouraged people around him to

learn Chinese. For example, he subscribed to Short Story

Monthly (小说月报)

for a whole year so that he could help ‘A’Jin’ (阿津),

his peer from Taiwan, to study modern Chinese. As for family

communication, according to Liu’s children, Liu taught

them the Shanghai dialect and Taiwanese instead of Japanese

when Liu’s wife and children moved to Shanghai in 1934.

Given the relations between Taiwan and Japan, … Liu’s

modernist writing can be regarded as an escape from Japan’s

assimilative colonial policy and Japanese literature, or a

protest of the colonized against the colonizer. By creating

Chinese modernism in China’s mainland via Japanese modernist

writings, Liu conquered the double challenge of Japan’s

colonial language policy and Taiwan’s old literature,

finally converging into the tradition of China’s modern

literature. Liu’s insistence on writing in Chinese and his

persistent interest in participating in the modern Chinese

literary arena formed the basis of his national

identification with China. This is the facet that has

been exclusively stressed in contemporary literature reviews

in Mainland China.

The Fragility of Modernist Writing

Ironically, Liu’s writing in Chinese also reveals the

ambiguity of his identity. The novelty of Liu’s

modernism was largely achieved by borrowing Japanese

concepts in his grammar and vocabulary development. This

fully demonstrated Japan’s colonial influence on Taiwan and

also in turn on Chinese modernist writing. The formation of

Chinese modernist writings was forged by the colonial

relationship between Japan and Taiwan, leaving remarkable

colonial scars in both languages. In the short stories

translated by Liu, specific Japanese characters can be found

everywhere. … some were even grammatically modified, or

exotically embellished with a ‘foreign tone.’ For example,

when studying Liu’s translation of Japanese

Neo-Sensationalists’ writing, it is easy to find that in the

original Japanese version, the ‘foreign tone’ was not

necessarily evident from beginning to end, however, once

translated by Liu, the proportion dramatically increased.

In other words, Liu introduced an exotic flavour that

could not be found in the original Japanese versions.

For example, Chinese term

葬礼

(zang li) which means funeral was expressed by Liu in the

Japanese term葬式

(sōshiki). The Chinese term

一分

钟

(yi fen zhong), meaning ‘one minute’, was expressed as the

Japanese term

一分间

(ippunkan). As such,

葬式

and

一分间,

both Japanese characters, were preserved by Liu Na’ou

without differentiation. In Liu Na’ou’s “Erotological

Culture”, there is a translation that literally reads ‘to

take out the words about food’ (把关于食物的话拿出来).

This is actually another example of translating Japanese in

an ‘exotic’ way. The corresponding Japanese compound word

for

拿出来

(to take out) is

持ち出す

(mochidasu) which has many meanings, including “to take out”

and ‘to start talking’.

In this context, it should be translated into ‘to start

talking’ rather than ‘to take out.’ This extraordinarily

exotic usage was not only confined to translations.

Conversely, it was scattered throughout his own fiction.

Take the following

:

“The Russian who is selling newspapers brings out a page of

foreign language in front of him. The front page is a

foreign emperor’s coronation ceremony. However, what is the

relation between the coronation ceremony of a foreign

emperor and the life of people in this country? Jing Qin

wonders whether it deserves such a huge report.” (卖报的俄人在他的脸前提出一页的外国文

来了。头号活字的标题报的是外国的皇帝即位祝贺式的盛况,但是外国

的皇帝即位跟这国的这些人们有什么关系呢,镜秋想,那用得到这么大

的报告吗)

In this short quotation, in four places the Chinese words

have been replaced with Japanese words:

提出

(teishutsu, bring out),

外国文

(gaikokubun, foreign language),

祝贺式

(shukugashiki, ceremony) and

报告

(hōkoku, report). Although similar in appearance to the

Chinese characters and imbued with almost the same meaning,

these Japanese words provoke a feeling of alienation in the

Chinese context.

Even the titles of articles

were imbued with Liu’s particular tone of writing. In the

August 25, 1935 issue of Women’s Pictorial (, with Liu as

editor in-chief, an article appeared, titled ‘Problems

Confronted by Chinese Cinema’ (

中国电影当面的问题).

当面的问题)

“Problems Confronted” is a transplantation of a typical

Japanese expression

当面の問題

(tōmen no mondai). Analysis suggests that the Chinese

modernist writing of Liu was mostly realized by substituting

Chinese with Japanese. Such borrowing of Japanese

expression rendered Liu’s texts as exotic as foreign

writings. The linguistic borrowing and transplantation

reflected in Liu’s works was not his voluntary choice but

resulted from his particular cultural…. Growing up in

colonial Taiwan and the experience of studying in Japan

affected Liu’s acquisition of Mandarin. Liu’s close friend

Shi Zhecun recalled that Liu’s Chinese was so awkwardly bad

it was as if he were writing Japanese.

This experience of writing in the Chinese language also

affects the plots of Liu’s writing, which can be read

as a reflection of his bewilderment over his own national

identity. Liu kept wandering between different cultural

and geographical boundaries. This disjunction is

reflected in the hero and heroines in his fiction who are

often single and have no connection with their families.

They are strangers: they have no knowledge of each other’s

past and future; they simply encounter each other at a

specific time. What they care about is ‘Now’. Day and night

they haunt the public consumption space in the city,

possibly “walking on an insensible road”, “from the race

club to teahouse”, or “from tea house to the busy street”,

“five minutes later”, they may appear “in one corner of the

dim ball hall”.

[…] considering Liu’s personal experience and the linguistic

ambiguity demonstrated in his works, these segments capture

the essence of Liu’s life as a colonial writer [...] the

disjointed images and a writing experience coloured by

dichotomous national boundaries further deepened Liu’s

personal alienation and sense of homelessness. Once

embodied in writing, this feeling of exile constitutes a

view of some fragile semiotics morphing together. This

apparent lack of coherency and consistency, which is

regarded as one of the hallmarks of modernist writing, was

not merely a novice’s literary experiment related to the

cultural importation from Japanese Neo-sensationalism but

the result of the cultural and psychological influence of

colonialism within Asia.

As Liu recorded in his diary in July and August 1927, …

Liu was plagued by neurasthenia and insomnia to such an

extent that he mentioned committing suicide in his diary.

Half of the space in Liu’s diary in 1927 was consumed by his

ongoing complaints about his neurological disorders. This

deteriorated

further when he was shocked by the news of Japanese famous

writer Akutagawa Ryūnosuke’s suicide. Yu Dafu (郁达夫),

a writer of the Creation Society that Liu so highly

endorsed, stated, his life “was a pursuit of sensory

pleasure when one was too depressed to feel the happiness of

life.” This mode of living, which was spiritually decadent

and preoccupied with seeking pleasure, was described by Yu

as fin-de-siècle aestheticism (世纪末思潮)

in China, a type of Chinese modernism similar to its

European counterpart. Liu, along with other writers of the

Creation Society, shared the same processes of sinking into

self-doubt and anguish, of modernity and a trend towards

seeking pleasure while their hearts were steeped in gloom.

Liu had in addition to contend with a feeling of

rootlessness engendered by his colonial experience, and

this was beyond the understanding of Chinese native

intellectuals living in Shanghai. The male protagonists

in Liu’s stories were characterized by the same amount of

melancholy and frailty. This in turn reveals Liu’s own

psychological state. They were ignored by ‘modern’ girls

because they still observed the outdated morality of the

patriarchy. Some, like the protagonist Bu Qing in “Games” (游戏),

were too preposterous, too sentimental and too romantic.

Others, like Jing Qiu in “Flow”,

wallowed in immeasurable melancholy, and spoke as though

they were composing a poem. The protagonists were pursuing

not only modern girls but also a time beyond their

capability. Rather than looking at Liu’s stories as

reflections of a kind of total moral decadence …, I suggest

regarding these protagonists, who seem unable to catch up

with the present, as incarnations of Liu’s anxiety

concerning the sense of time, a failure to connect the past

with the future. In a word, the figures under Liu’s pen,

such as the modern girls who are out of reach and the male

protagonists who suffer from incomprehensible

sentimentality, reflect Liu’s uneasy soul and unrestrained

anxiety. Similar to Japanese Neo-Sensationalism, which

emerged after the Great Kantō Earthquake in 1923, Chinese

modernist writings were also generated in a loose

atmosphere. The difference was that the decadent atmosphere

of Chinese modernistic writing was in part resulted from

Japan’s colonization of Taiwan.

[…] The writing style of image juxtaposition not only

indicated Liu’s innovative form but also his psychological

status. The vagueness and rupture of Liu’s use of language

would probably have influenced his recognition of national

identity. Identities are negotiable, and subject to

mutations and changes. […] As a component of national

identity, language can both affirm and deny certain national

identification, not necessarily generating an imagined

community. Liu Na’ou’s short stories were created mainly in

the two years from 1928 to 1929, when he first sojourned in

Shanghai. Except for his sporadic writings between 1932 and

1934, no new literary works appeared after 1934; and

almost no movie reviews or journal publications after 1935.

It may have been that with the further strengthening of the

imperialist aggression against China and the deepening of

Liu’s awareness of his own situation, his persistence in

China, or rather in modernism, disappeared along with his

initial arguable Chinese national sentiment. Therefore,

neither the Chinese nationalism nor the cosmopolitanism, two

opposite stances in the contemporary debate over how to

define Liu’s writing and his identity, offers sufficient

summary of his writing. Instead, a new framework of

“intertwined colonization” and the inner triangle of China,

Japan and Taiwan, reveals the complicity and tensions

between these two ends.

Reflection on modern Chinese literature

Although Shi Zhecun … indicated that Liu wrote in Chinese as

if he was writing in other foreign languages, was the

novelty the only reason the reading market accepted his

works? The situation might be even more complex if the

development of new literature and language reformation in

China is taken into account. Liu’s writing was tolerated and

even embraced in China around 1928 perhaps also because of

the immaturity of the Chinese national language and

Chinese

modern literature which started to develop only after the

late 1920s.

[…] ‘Being Chinese’ requires a device for producing “a

palpable sentiment of nationality” which further depends on

the creation of “a mother tongue”, a native language, or a

national language. This argument is largely valid whether in

the case of the Japan that Naoki studies or in the case of

Europe which is Anderson’s focus. The rule also can be

applied to the process of Chinese modernity and the

modernization of Chinese literature. […]

Nation building in China entailed a process of reforming

both modern Chinese language and modern Chinese literature.

The naissance and reformation of China’s modern language can

be traced back to 1887, when Huang Zunxian (黄遵宪

1804–1905) highlighted the importance of the consistency

between oral words and written words in his “Record of

Japan” (日本国志).

After that, the will among Chinese intellectuals to reform

modern Chinese was unwaveringly sustained until the pinnacle

of Chinese nationalism of the May Fourth Movement finally

arrived. Although the subject of national language entered

the curriculum of elementary schools in 1913, the setup of a

similar subject in middle schools was only realized as late

as 1923. The textbooks for the education of national

language used in middle schools in 1925 were occupied by

essays and short stories such as “Hometown” (故乡)

written by Lu Xun, whose works cannot be said to be written

in an exemplary modern Chinese. The modernization of

Chinese went through a long period of several decades,

even extended into the post-war periods under the

supervision of Mao Zedong. It is obvious that amid the

promotion of vernacular, many official documents and

newspapers were still written in classical Chinese. The

1920s was located in the initial stage of this long process.

In other words, the 1920s still saw a certain degree of

flexibility and multiplicity in written Chinese. In

this broadly experimental environment, Liu’s novel, albeit

impure, found its place. The paradox of modern Chinese

is that on the one hand, “modern Standard Chinese, Putonghua

Mandarin and Guoyu Mandarin have been set in opposition to

local language as the signifier of the historical past”,

while on the other hand, the history of the standardization

of the Chinese national language is unable to eliminate the

local elements which were prevalent in literature and the

media. The paradox can be further complicated if ‘locals’

are historicized in a colonial context.

Chinese modern literature … cannot be reduced to a national

facet of homogeneity; rather, it contains various

heterogeneous voices serving as the signifier of various

historical pasts, among which is the modernist literature

rendered by Japanese colonization. Liu’s writing involves

variations that could not be simply reduced to the Chinese

written language, and these deviations only can be

understood in the process of historicizing Chinese modernist

writings in “an intertwined colonial situation”. These

variations in modern Chinese and the incommensurability of

modern Chinese and the sentiment of Chinese nationalism can

lead to a possible reflection, by using an Asian example, on

the “discontinuity-in connectedness” raised by Anderson.

According to Anderson, the concrete formation of

nation-states is “by no means isomorphic with the

determinate reach of particular print-languages”. The

discrepancy between print-language, the national

consciousness, and nation-states results in the so-called

“discontinuity-in-connectedness”, which is evident in

nation-states of Spanish America, the “Anglo-Saxon family”,

and many ex-colonial states such as Africa.

Yet, this “discontinuity-in-connectedness” can also be found

in modern China … Liu’s Chinese writing, which was mixed

with Japanese in various levels, … reached a symbolic realm,

signifying a cultural and historical specificity. The

impurity of Chinese modernist writing should not be reviewed

merely in the rigidly demarcated borders of China; it ought

to be understood in the cultural interchanges between China

and Japan. It reveals not only the political and social

influence of the colonial encounter between Japan and Taiwan

but also the influence of a rising Japan within Asia. In her

“Translingual Practice”, Lydia H. Liu offers many good

examples of

Japanese loanwords in modern Chinese to demonstrate how

Chinese intellectuals managed to speed up Chinese

modernization by introducing modern European concepts via

Japan

.

Similarly, although the initial interest in phonetic writing

of Lu Kanchang … was aroused by the Romanizing activities of

the missionaries, his later work was inspired by the

Japanese linguistic system.

Nevertheless, centuries before Chinese nationalists reformed

the Chinese language by the emulation of Japan due to their

admiration of Japanese achievements, it was Japan that

imported Chinese cultural and characters from China. […] the

origin of Japanese writing derived from Chinese books such

as the Confucian Analects (论语)

and Thousand-Character Classic (千字文).

Yet, when it came to the Edo period, the school of national

learning (国学者)

denounced the influence of Confucianism and tried to revive

Japanese by rejecting the use of Chinese words and Chinese

characters in Japanese. The attitude toward Chinese

characters and the corresponding confidence in Japanese

language were further developed to an extreme degree,

encapsulated by the idea of making Japanese the Asian common

language in 1941, with the establishment of the Greater East

Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. In modern Asia, the enthusiasm

among Chinese nationalists for absorbing and borrowing

Japanese words was diametrically the opposite…. Liu’s

modernist writing, a direct result of an output of Japanese

into China after 1905, can be read as the reification of the

changed power structure of Asia, specifically, the

diminishment of Chinese cultural power and, conversely, the

rise of the Japanese empire. Therefore, inspired by Arif

Dirlik’s articulation of the relations of power when

studying the discourse of Orientalism,59

the Chinese

modernist writings of Liu were a product of the unfolding

relationship between countries of Asia, reflecting a process

of power shifting. It is an issue of political and cultural

interactions of East Asia instead of a problem only

pertinent to Chinese literature.

Extrait de l’article : Between the National and

Cosmopolitan: Liu Na’ou’s Modernist Writings, by

Ying Xiong

Literature & Aesthetics 20 (1) July 2010. (article

en ligne, à télécharger en PDF :

4914-241-8381-1-10-20110915.pdf)