|

|

Chinese

literature: what to read and how to read it

By Brigitte Duzan - January 6, 2017

Questions about how to choose what to read when willing to read

Chinese literature, and especially fiction, are recurring ones.

But the problem is not only what to read, it is also

how to read.

Reading entails from the start a double problem: a problem of

selection and a problem of appreciation. For a foreign reader

trying to read Chinese literature, this double problem is a

daunting one, made all the more difficult by the cultural gap,

which starts with the language.

Originally conceived as a blog and developing into a website,

http://www.chinese-shortstories.com/

was created with a view to helping bridge that gap, based on a

few key ideas, including the conviction that online publication

is the most efficient, most flexible way of gradually building

up what is meant to be, in a fluctuating future, a kind of

literary encyclopedia, that is a guide to reading.

But it is a selective one, reflecting personal readings,

research, and aesthetic tastes. And starting from two main

assumptions.

Assumption one:

being non-Chinese, you don’t read a Chinese book the way you

read any other book pertaining to your own culture. You can, but

you often lose the gist of the story, be it fiction or, still

more, non-fiction.

|

Chinese literature has indeed a universal appeal, based

on shared longings, sufferings, fears, simple joys,

bitter frustrations, and a similar human fate. Anybody

can sympathize with a grieving mother, a dying soldier,

an elated lover, an aging artist, and generally the

common man around the corner, which might be your own

neighbour.

Even the most ancient Chinese poems, those mostly

anonymous of the Book of Songs (or Classic of

Poetry) dating to the 11th to 8th

century BC, are for a good part short pieces recording

the voice of the common people like common people

everywhere, with joys and sorrows, and little hope for

Heaven’s support or the King’s benevolent help.

The difference comes with the expression of those

feelings, which makes it unique, unique as individual

expression, but |

|

|

also as part of a culture which gives it a certain resonance. In

that sense, the best Chinese literature has this same special

quality as the ancient Chinese shanshui

paintings, landscape paintings of "water and mountain" which the

literati perceived as part of an inner experience, something

that has to resonate with your own feelings, deep at the heart

of your own self.

In that sense, too, this brings us to the second assumption.

Assumption two:

anybody wanting to read a Chinese book does so because he or she

has at least a vague interest in China, the country and its

people.

The nature of this interest will direct the eventual choice to

be made among a vast array of available titles. It is therefore

best for any reader to be able to have a good idea of the

content and style of the book, but also of the author’s

personality and of the context of his writings. And knowing more

about all of this will then help the reading too.

The first choice to be made is about the period:

classical literature or modern and contemporary literature. Both

are a reflection of their time, but written in a totally

different language, a difference that may however be partially

erased in a translation, especially given the tendency to

“smooth” a text as you smooth wrinkles.

In its first approach,

chineseshortstories’

main interest focuses on modern and contemporary

literature, because it gives the most vivid image of

present-day China, but also because it is a rich period of

experiments, starting with the language, from the beginning of

the 20th century which saw the birth of the

vernacular

baihua,

at the end of the 1910 : a new form of expression closer to the

spoken language and closer to a broader readership than the

literati of yesteryear, the field of experiment being the

short story.

|

Under the auspices of Lu Xun, the short story then

became the ideal mode of expressing sharp social

criticism, and, as time went by and the failure of the

1911 Revolution became clearer by the day, increasing

disillusion, grief, and qualms about the future.

Not that it was something unheard of; the short story is

in fact the origin of fiction in China. The first

stories, as fiction, found in ancient texts dating back

even before Christ, were labelled xiaoshuo,

literally “small talk”, gossips and chatter that the

literati frowned upon and despised, as they despised the

popular novels which began to appear in the 13th

century, based on folk tales of lore.

So it was a revolution of sorts when Lu Xun paved the

way for that same short story to become the foremost

mode of |

|

|

expression of the Chinese intellectuals of the 20th

century, but revolution in literature was but one of the

revolutions of the time.

The

short story came back to the fore after the Cultural Revolution,

at the end of the 1970, when literature was revived and renewed.

The short story – and the novella growing in its wake for

narrative purposes – was then the crux of another round of

fruitful experiments following one literary movement after

another all along the 1980’s, until its apex, at the end of the

decade, in an avant-garde movement that was crushed not so much

by the fateful events of 1989, but by a new trend which led to

the development of commercial literature in the following

decade.

Writers were urged, by editors, to write novels, and they did,

giving rise to an unending flow of family sagas more or

less modeled on Ba Jin’s

Family,

back in the 1930’s, or Lao She’s Four Generations Under One

Roof, published in 1949. As these sagas chronicle the fate

of families in all kinds of areas of the country, and usually

span half a century from the end of the Qing Dynasty, they

constitute a vivid illustration of changing ways of life in

various parts of the land, as part of a historical process far

from the main events of the period as learned in history books.

But the 1990’ also saw the rise of novels praised by

Western critics, and readers, for their social and political

criticism, sometimes expressed in jocular fashion, which makes

them all the more attractive. These novels gave rise to a great

number of translations, and their authors became world-famous.

They include the 2012 Nobel Prize, Mo Yan, but others deserve at

least equal attention, although they might not have so many

available translations.

The trend continued well into the 2010’s, but times are changing

again. By the mid-2010’s, the novel is running out, and the

trend is again toward the short story and the novella, written

by young writers not so much of the riotous post’80 generation,

but by the much more mature generation of those born in the

1970’s, who are eventually achieving recognition. Each one has

his own style, but the majority of them build up a personal

universe based on recollections of the past, and inner feelings

about the present often hidden under a slight veneer of cold

humour.

They publish in a vast array of literary magazines all over the

country; the most difficult is to track them down, each

discovery, often haphazard, through hearsay or tip from a

critic, is the reward for the quest. And this quest is all the

more difficult that the best of the short story and novella

writers are now, in the last year or two, specializing in short

shorts, xiao xiaoshuo.

The xiao xiaoshuo has become the most refined, demanding

style, a cross of poetry, short story and essay. It is a new way

of writing, but with its own references in the past, especially

in one of the best Chinese writers of short stories ever, Pu

Songling, at the very end of the Ming period, a man of letters

who wrote in superb classical Chinese a collection of short

stories still considered a model today: the Tales of the

Liaozhai (from the name of his studio).

This is a perfect example of the way styles and genres evolved,

in China: even what seems revolutionary reflects an ancient

tradition, one way or another. This is a reason why, even if

your main interest lies in contemporary literature,

classical literature gives a useful framework, not only

for the sheer pleasure of its refined poetry and fiction, but

also because it offers a wealth of references and quotations.

This is the beginning of the story: how it all started.

Ancient legends, Tang Poems, Ming and Qing novels inform

present-day literature in a number of ways. Those are verses and

stories that Chinese children learn at school, and remember all

their lives afterwards; they become part of their inner world.

|

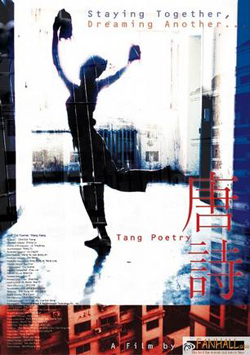

The film director Zhang Lü, for instance, titled his

first full - length feature “Tang Poetry” Tang Shi,

a subtle exercise on the solace found in poetry

remembered from the past in the dreariest moments in the

life of a young boy.

When asked about his title and subject, Zhang Lü

instantly replied, as if expecting the question: because

Tang poems are parts of our life, even in the most

difficult moment, there is always a poem, learnt by

heart, that emerges from the past, something of the

nature of dreams, that borders on the subconscious.

Some stories are old legends, creation myths, or just

anecdotes in serious books, some dating all the way back

to the Warring States period, some three or four

centuries before Christ, books like the Han Feizi

where they appear almost incongruous, but they have such

deep meanings that |

|

|

they morphed into everyday four-character expressions that are

to be found everywhere in today’s writings.

Classical pre-Ming and Ming novels are especially interesting as

sources of stories that are part, from the earliest age, of the

subconscious of the Chinese people: Water Margins (or Outlaws of

the Marsh), Journey to the West or Dream of the Red Chamber, to

quote only three. These are not only fascinating stories,

objects of the most serious research, they are also part of a

sort of common popular subconscious that pervades writing and

life.

Take the first one, for instance, a masterpiece of vernacular

Chinese written at some time in the 14th century, we

are not even sure by whom. This is the story of a group of

outlaws who escaped arrest and punishment, for crimes allegedly

committed for rightful purposes, by taking refuge in a swampy

region called the Liangshan marsh; they are described as

creating there a kind of unruly society, with its own codes of

honour, fighting against a foul government.

The story is

based on supposedly historical events recorded during the Song

dynasty, and evolved

from folk tales told by storytellers from the Southern Song on.

They are known as the Liangshan heroes, and some of the stories

are so famous that they are quoted for their symbolic value in

literature and films, even today…

The novel is part of a rich set of collective images dating

back, again, to the Warring States period: images of noble

swords men fighting for justice and the redress of grievances,

known as xia, at the core of the so-called wuxia

literature. A term that has such a deep and variegated meaning

that it is hardly translatable, as is the word for the Liangshan

marsh: the jianghu, literally rivers and lakes, with its

rich connotations of rightful rebellion and life at the margins.

A word that often appears in today’s literature in expressions

as simple as: this is very jianghu… which immediately

calls to mind a whole set of images and ideas as subtle,

pervasive and difficult to explain as the delicate scent of a

flower.

Chinese literature is a world apart that can be read for its

stories, but gains much more flavour when approached as a gate

to a culture, and part of that culture.

Suggested readings for a start

(available in English translation)

·

Ancient Classics

- The Book of Songs, The Ancient Chinese Classic of Poetry,

translated from the Chinese by Arthur Waley, and edited with

additional translations by Joseph R. Allen and foreword by

Stephen Owen, Grove Press 1996.

- How to Read a Chinese Poem: A Bilingual Anthology, by Edward

Chang, Book Surge Publishing, July 31st, 2007, 448p.

- Outlaws of the March, translated by Sidney Shapiro, Foreign

Languages (Library of Chinese Classics, bilingual edition),

January 1999, 5 vol.

- Three Kingdoms: a Historical Novel, att. to Luo Guanzhong,

unabridged edition translated by Moss Roberts, University of

California Press, June 2004, 2 vol.

- Journey to the West, att. to Wu Cheng’en, revised edition

(initially published 1983), fully translated and edited by

Anthony C. Yu, University of Chicago Press, 2012, 3 vol.

- Cao Xueqin, Story of the Stone, or Dream of the Red Chamber,

translated by David Hawkes, Penguin Classics, 1974, 3 vol.

- Pu Songling, Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio (published

only in 1766), 104 stories translated by John Mindford, Penguin

Classics 2006, 608 p.

·

Modern Classics

- Lu Xun, The Real Story of Ah-Q and Other Tales of China: The

Complete Fiction of Lu Xun (1918-1935), translated by Julia

Lovell, Penguin Classics, 2009, 416 p. Including Diary of a

Madman, Kong Yiji and other stories of Call to Arms Nahan,

plus Old stories retold.

- Ba Jin, Family (1931), novel translated by Olga Lang, with

long preface written by the translator in 1972, at the time of

her translation, Doubleday & Co 1972 (reprinted 1979), 329 p.

- Mao Dun,

The Shop of the Lin Family & Spring

Silkworms (Bilingual Series in Modern Chinese Literature)

(1932), translated by Sidney Shapiro, the Chinese University of

Hong Kong 2001 (reprinted 2003), 200 p.

- Shen Congwen, Border Town (1934), translated by Jeffrey C.

Kinkley,

- Lao She, Rickshaw Boy (1936), translated by Howard Goldblatt,

Harper Perennial 2010, 320 p.

- Zhang Ailing/Eileen Chang, Love in a Fallen City, (1943),

translated by Karen S. Kingsbury, New York Review Books Classics

2006, 321 p.

·

Contemporary Classics

Some Novels

- Wang Meng, The Bolshevik Salute (1979), a “modernist Chinese

novel” translated by Wendy Larson, University of Washington

Press 1989, 174 p.

- Mo Yan, Red Sorghum (1986), translated by Howard Goldblatt,

Penguin Books 1993, 359 p.

- Jia Pingwa, Ruined City (1993), translated by Howard Goldblatt,

University of Oklahoma Press 2016, 536 p.

- Yu Hua, To Live (1993), translated by Michael Berry, Anchor

2003, 256 p.

- Wang Anyi, The Song of Everlasting Sorrow, translated by

Michael Berry and Susan Chan Egan, Columbia University Press

2010, 456 p.

- BiFeiyu, The Moon Opera (2000), translated by Howard Goldblatt,

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt 2009, 126 p

- Yan Lianke, Dream of Ding Village (2005), translated by Cindy

Carter, Grove Press 2011, 352 p.

Short stories and novellas

- Wang Anyi, Love on a Barren Mountain (1987), novella

translated by Eva Hung, Renditions Paperbacks 1991, 143 p. (1st

part of a “love trilogy”)

- Han Shaogong, Homecoming? and other stories [including PaPaPa

(1985) and WomanWomanWoman (1986)], four short stories

translated by Martha Cheung, Renditions Paperbacks 1992.

- Ge Fei, Flock of Brown Birds (1989), translated by Poppy

Toland, with a preface by Ge Fei, Penguin Specials 2016, 96 p.

- Ah Cheng, Three Novellas: King of Trees, King of Chess, King

of Children (1984, 1985), translated by Bonnie S. MacDougall,

New Directions 1990/2010, 208 p.

- Liu Xinwu, Black Walls and other stories, ed. by Don J. Cohn,

Renditions Paperbacks 1990, 202p

- The Time Is Not Yet Ripe, Contemporary China’s Best Writers

and Their Stories, ed. by Ying Bian, Foreign Language Press,

Beijing 1991, 382 p. (Ten short stories of the 1980’s with

introductions by Gladys Yang, Li Jun and others)

- Su Tong, Madwoman on the Bridge, 14 short stories translated

by Josh Sternberg, Black Swan 2008, 304 p.

Afterword

Short stories are underrepresented in available translations in

English. There are more translations available in French for the

period 1980’s-1990’s, thanks to the awareness, then, of several

publishers and translators,but novels have since taken over,

with the exception of some novellas requalified as short novels.

Publishers still live with the assumption that short stories

don’t sell.

Book publications must therefore be supplemented by literary

magazines, such as Renditions (Hong Kong), Chinese

Literature and Culture (New York/Guangzhou), Chinese Arts and

Letters (CAL, Nanjing), which complement translations with

useful articles about the writers and their works. Chutzpah/Tiannan,

launched by Ou Ning, was an invaluable source of discoveries of

young emerging writers while it lasted; published issues,

including translations, remain precious.

Chinese short stories, and novellas, have long been the basis of

Chinese fiction, and have recently gained new ground among young

writers. They are one of the best introductions to Chinese

literature, and to Chinese society, for a great many readers, as

well as a way to deepen their knowledge of the Chinese language

and culture for those who study it. This is where such

initiatives as Pathlight, Read Paper Republic or

chineseshortstories

find their worth.

Then, when all is said, and read, another way to appreciate, and

sometimes discover, Chinese fiction is to look into film

adaptations, as Chinese cinema, from its very inception, has had

close ties with literature. That was one of the reasons for the

launching of the twin website of chineseshortstories:

http://www.chinesemovies.com.fr/

But that would be another story…

|

|